"Everything in this country is socialist!"I dined late last year with a visitor to Australia's shores, who, as you might tell from the brief exchange above, had reached (in his mind) a damning conclusion about Australia. Its institutions, its people, its very DNA all smelt of socialism.

"Everything?"

"Everything. Your health care system. The ABC. Your university admissions. The fact that you have a minimum wage. It's all socialist!"

Admittedly, compared to the homeland of my fellow dinner, Australia is in a unique position. Many of our institutions are in public hands (and when I was a kid many were publicly owned, such as the Commonwealth Bank, Telstra, The State Bank in NSW, etc.), and many aspects of our welfare system, such as Medicare, have taken on the status of an institution, such that it would be close to politically impossible for a government to dismantle them.

However, rather than socialism, I suspect that these aspects of Australian society bear witness to an older political tradition. We are called ‘the Commonwealth of Australia’, which oddly at first only looks as if we share riches, as in ‘common wealth’. This is, of course, partially true: we do share riches in terms of participating in an economy, and using common infrastructures. But that economic truth is only one aspect of a deeper truth that was once being expressed by this term. ‘Wealth’ comes from an older word for what is good, ‘weal’, hence a ‘commonwealth’ was always meant to be about a society of people committed to a ‘common good’.

Just pointing out the name of the country does not nothing on its own. However, Andrew Cameron has argued that 'The fact that we were called a ‘Commonwealth’ indicates that there has been an alternative tradition at work in Australia: the concept of a community who seeks together for a good life, in quality relationships with one another.'

[There is a long Christian history of the common good drawing on the significant New Testament word koinonia, which can traced, among other places, in Oliver O'Donovan's short book Common Objects of Love.]

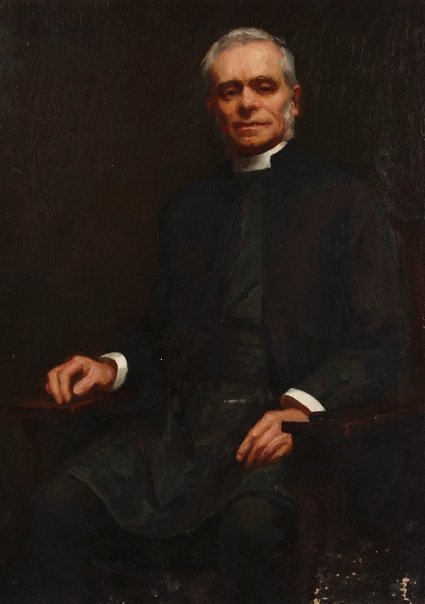

Arguably, it is this concept of society which drove the introduction of the pension in NSW. One of the significant forces behind the introduction of old-aged and infirm pensions in NSW was the Ven. Francis 'Bertie Boyce and the now defunct the parish of St Paul's Redfern. Boyce was hardly a socialist; as the founder of the British Empire League, he tirelessly campaigned for the observance of Empire Day in NSW - it helped that the Premier of NSW was a member of St Paul's. Boyce also founded the Anglican Church League, the conservative evangelical lobby group in the Sydney Diocese.

It may come as a surprise to you then that Boyce was the leading social reform advocate in NSW at the turn of the 20th century, covering issues such as woman's suffrage, slum clearance, and temperance. Boyce has advocated for years on the issue of an old aged pension. The introduction of the pension was a significant moment in NSW, as it had by and large been the responsibility of the church to provide relief for the aged. Yet Boyce did not see this as a straight handing over to the state the relief work which had traditionally been the purview of the churches. Preaching at St Paul’s Redfern just after the introduction of the pensions into NSW, Boyce described the expected £60,000 p.a. cost of the pension as ‘a Christian contribution to suffering humanity.’

Whereas the church had previously been limited by its connections with those in need and its own fundraising, for Boyce the government's new found responsibility to provide the pension would move beyond the limited connections any one church might have and enable as many people to be cared for in their twilight years. Reflecting on Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2, Boyce argued that this would give the Christian all the more reason to pay their tax, and to see their tax used in the service of those in need by God's own ministers.

At a time when we read about individuals and corporations peddling their money through overseas tax havens, Boyce's approach to tax and welfare seems entirely foreign. And yet, it's beautiful, and based on a generous ecclessiology - that the church exists as the pillar and bulwark of truth to extend God's blessing to all people in society.

Far from socialist, the bedrock for Australia's great institutions rest upon a Christian concept of of community.

1 comment:

Thanks, Matt--really appreciated this post as I feel I have similiar conversations about this "socialist paradise" (the designation of choice of many of my interlocteurs).

Post a Comment