One of the interesting questions that will be posed this year now doubt will be 'how do we apply the reformation truths/achievement to today?' What is 'the reformation we need to have'?

So here is a little thought experiment we might try on. If you were running a conference on that question, how would you go about it? You might use the five solas as a way of examining the nature of the reformation. Or you might use Barth's phrase Ecclesia semper reformanda est to consider the need for reform in today's church. One might even use the ordo salutis.

The difficulty is that what was kindled in 1517 (or 1510 if you date the reformation from the commencement of Luther's Psalm lectures) spanned several decades (until at least 1689 when the spirit of reform settled into apathy and latitudinarianism, only to be rekindled in the 1730's), across nations, languages, and social strata. At various stages it sought modify and confirm to Biblical truth the nation, the church, and the personal life. It was a movement which spawned various branches, each of which were diverse and complex.

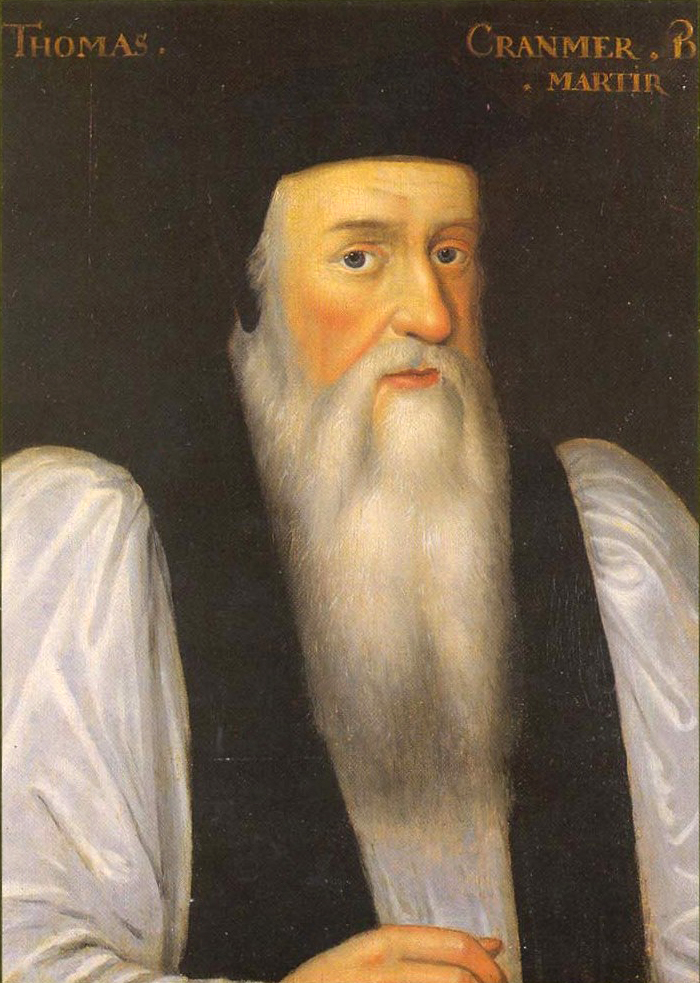

However, despite the variegated nature of the Reformation, what Luther, Zwingli, Bullinger, Bucer, Cranmer, and others achieved was a return to a biblical economy of grace. Following Augustine, the medieval and early modern church had developed a concept of grace, (i.e. prevenient grace, cooperating grace, sufficient grace, and efficient grace) which were obtained through various ecclesiastical structures and systems, and mediated through the priestly caste.

The reformers rediscovered the radical, irresistible nature of saving grace. They reveled in it. It shaped their ministry. It shaped their lives. It shaped the way the sought to return to evangel. They rediscovered that God's move towards us in Christ is an act of sheer, unmerited, unadulterated, grace. A gift, by which the trajectory of their lives was irrevocably tied to Christ's. And it thrilled their hearts.

If it was up to me, the concept of grace would be the controlling concept for such a conference. It also has the advantage of placing the Reformation in context and continuity with Augustine – the Doctor of Grace – on the one hand, and who we know of in the English speaking world as the evangelicals on the other (John and Charles Wesley, George Whitefield, and Jonathan Edwards).

So here is what I would include in such a conference:

i. The Reformation and the Economy of Grace

ii. The Allurement of Grace

iii. The Exposition of Grace

iv. The Life of Grace

v. The Unity of Grace

vi. Grace Works

vii. Common Grace and the Common Good

viii. Dis-Grace in the Reformation

ix. Witnessing to the Word of His Grace

Let's take a brief moment to examine what each of these may consider:

The Reformation and The Economy of Grace

There are lots of competing theological ideas which might compete for the central focus of reformed thought: justification by faith, the cross, God's sovereignty and election, the sufficient of scripture. And fair enough; at different points each of these where flash points of contention during the reformation. But what ties each of these together is the reformed understanding of grace. It was the rediscovery that not only could a righteous God justify sinners, but that in Christ he would justify the ungodly which mobilized the reformers. It was the rediscovery that God condescend himself to speak (with perspicacity) to people like you and me. It was the rediscovery that God had condescend himself to take on flesh and walk among us, and that the sacraments where a means of remembering and participating in that act of grace. And it brought down the whole stinking mess of indulgences and purgatory, sacerdotal mediation and magisterial authority. This session would be placing the Reformation in this historical, philosophical, and theological context, laying the groundwork for the rest of the conference.

The Allurement of Grace

According to Ashley Null, this was central image for Thomas Cranmer and other Reformers. God makes the dead come alive by captivating their hearts, and enthralling their imagination. So this really about the significance of the heart in Protestant thinking and the dynamics of grace renewal.

The Exposition of Grace

Whilst preaching had been a feature of the medieval Christian world, particularly through the influence of the friars, the Reformation inspired the regular teaching of the whole counsel of God through the literal sense of Scripture. This did not dull the Reformers to the allegorical or tropological senses. But it did highlight the significance of regular exposition of God's word for spiritual health and growth. In the Anglican context, whilst the focus of the service lay by and large in the public reading of Scripture, Cranmer determined that there was always to be an exposition whenever the Lord's Supper was celebrated, and prepared homilies accordingly for priests who required such assistance. Meanwhile Calvin and Luther were appreciated for their sermons, commentaries, and lectures on Scripture as much as they were their doctrinal work. This session would consider the significance of the reformed commitment to preaching for today's church practices.

The Life of Grace

The Reformers offered a vision of life lived under grace. From Tyndale's hope for the ploughboy to read and understand scripture, Calvin's doctrines of union with Christ and the work of the Spirit in shaping the moral imagination of the believer, Luther's depiction and embodiment of marriage, to the rending of the sacred-secular divide, the Reformers depicted the ordinary life of the believer as an avenue to honour God. Christ sanctified the ordinary. This session would need to examine the place of the sacraments as means of grace in the life of the believer, given how significant they were for the Reformers, and how fallen by the way side they have become in some churches today.

The Unity of Grace

Breaking with Rome as no easy task; the Reformers cared deeply about church unity and catholicity, and established international networks of Christian partnerships. Indeed the stressed that they, and not Rome, where fulfilling the vision of catholicity even when they allowed for diversity of practice. The Reformers cared about church unity, undoubtedly more so than we do that. What might they teach an age marked by denominations, tribalism, and insipid ecumenism?

Grace Works

An expansion of the 'Life of Grace' session, the Reformers cared deeply about the integration of faith and work. From the prince to the milkmaid, the soldier to the cobbler, they understood that our work matters. Thomas Cranmer in particular, following the advice of St Basil the Great, developed the Book of Common Prayer as a means to encourage the 'commons' in the work of their hands. Where might this commitment lead us today?

Common Grace and the Common Good

So if the most significant reflection ever given to the place of non-Christian wisdom is to be found in the opening chapters of Calvin's Institutes. In preaching saving grace, the Reformers also believed in God's common grace shown to all people. This in turn spurned them on to the love and welfare of society in general. Whilst our situations are different, this session will consider the implications of those convictions for our context today.

Dis-Grace in the Reformation

Among the many achievements of the reformation were moments of petty squabbling, ugly division, and brutal coercion. As the heirs of the Protestants, what might we lead from their mistakes?

Witnessing to the Word of His Grace

The Reformers were concerned that true religion would awaken the dullest hearts. They wrote Latin essays for the learned, tracts in the vulgar tongue for the gentry, and drama for the unlearned men and women of the land. Even Cranmer, preparing liturgy at a time when church attendance was mandatory, was actively aware of the need to reach the unchurched and the ungodly. The zeal of the Reformers inspired those who came after them in the Great Awakening of the 1730s. Where nigh that same concern and zeal take us today?

That is nine session. Are there things that you would skip? Or things that I've missed?