Making Sense of a Hostile World

Intro | Part I | Part II

“Jesus had fulfilled Israel’s vocation to be a light to the nations; now the nations must be brought into allegiance to him. It was time for the nations to join in God’s promises Abraham.”

In the previous post in this series, we briefly sketched out why the Jewish worldview is important for understanding the early church. It made sense of how the early church understood Jesus (the risen promised King of Israel), and why they launched on an ambitious and frantic mission to proclaim his lordship throughout the Roman Empire, and even beyond imperial borders.

This all made sense with a Jewish worldview. But as the end of the first century approached and the first generation of church leaders died, would we see the worldview of the church begin to morph away from the Jewish-ness of the church’s foundation? This is a question commonly poised in church history – and the assumed answer is often a definitive yes. After all there were more and more gentile converts coming into the church; and in 136 AD Roman armies crushed the last great Jewish rebellion against the Empire (the

Bar Kokhba revolt AD 132-136), thereby drawing to a close the world of second temple Judaism. The second century church would belong to the gentiles.

Except that I’m not sure that is quite what happened. From the available evidence it seems as though the church’s mission was still focused on both Jews and Gentiles. And in fact large numbers of Jewish converts were still being well into the third century. Furthermore, as the church dealt with several crises during the second century, it did so in a thoroughly Jewish way. Don’t misunderstand me: the church’s worldview was thoroughly shaped on and around Jesus Christ; it was a distinguishably Christian worldview when contrasted to the rest of Judaism. But it was still Jewish: God was the creator of the world. In response to evil he called Abraham and made promises about his descendants (Israel). Jesus was the climax of

this story. And it was

this story that enabled the church to negotiate an aggressive and often hostile world around them.

As the apostles died, leadership of the church for the next two generations passed to a group that we know as the apostolic fathers. These men were active from the end of the first century through to the around 150AD, and had been taught and served alongside the apostles. We have the writings of the several of the apostolic fathers, such as Clement of Rome (who wrote an epistle to the Corinthian Church around 90AD), Polycarp of Smyrna (who was martyred in155AD) and Ignatius of Antioch (who wrote several letters to churches in Asia and the church leader Polycarp as he travelled from Antioch to Rome to be martyred in 110AD). There are other apostolic fathers such as Papias, who wrote quite extensively but, except for a few fragments that have survived in other works, are now lost to us. And we have some anonymous documents such as the Didache and the Shepherd of Hermas.

Following the apostolic fathers the middle of the second century was dominated by a group of men we know as the apologists such as Tertullian (the first Christian to write extensively in Latin) and Justin Martyr who wrote quite extensively in defence of Christianity against “pagan” elites”, and often write appeals to the emperors requesting an end to persecution. By the end of the century the church is being lead by a diverse range of bishops and leaders i.e. Irenaeus, Melito of Sardis, and Clement of Alexandria (who taught in the church’s first Catechetical school and started to integrate Greek philosophy with Christianity). Throughout the second century Christianity was focused on the urban areas of Palestine, Syria, Egypt, Asia and the surrounding provinces (Turkey), Greece, Italy, and Mesopotamia. The church had also started to grow throughout Carthage/North Africa and Gaul.

Martyrdom and the Gnostics

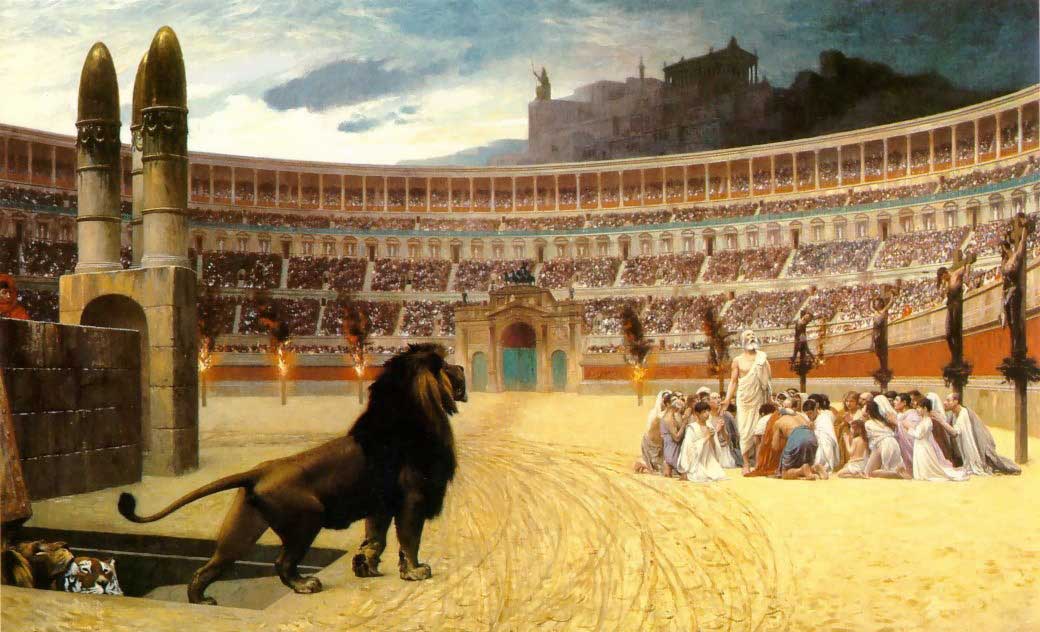

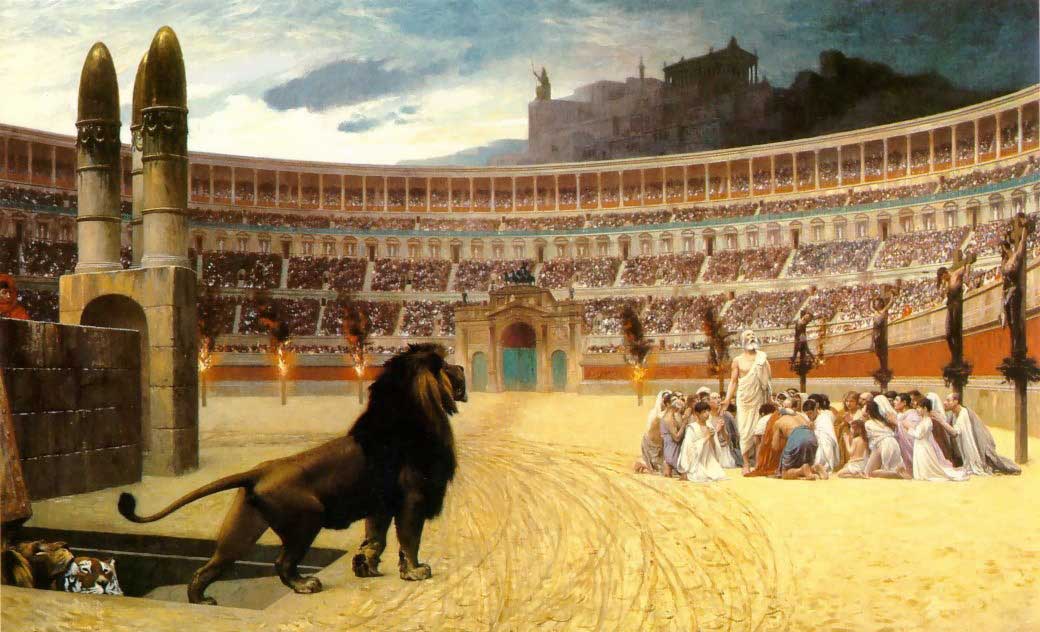

Although there had been sporadic localised persecution throughout the first century, by 125AD it became Imperial policy to punish Christians. Largely focused on the church’s leadership, the persecution of the second century was still quite sporadic compared to the large scale martyrdom's of the late third and early fourth centuries. Yet the example of second century martyrs was still so powerful for the church in strengthening the resolve of the flock and winning new believers that Tertullian could write:

“The more you mow us down, the more we grow. The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.”

The Christians were prepared to die for their faith. Ignatius of Antioch even wrote ahead to the Roman Church to ask them not to intervene:

“I am writing to all the Churches and I enjoin all that I am dying willingly for God's sake, if only you do not prevent it. I beg you; do not do me an untimely kindness. Allow me to be eaten by the beasts, which are my way of reaching to God. I am God's wheat, and I am to be ground by the teeth of wild beasts, so that I may become the pure bread of Christ.”

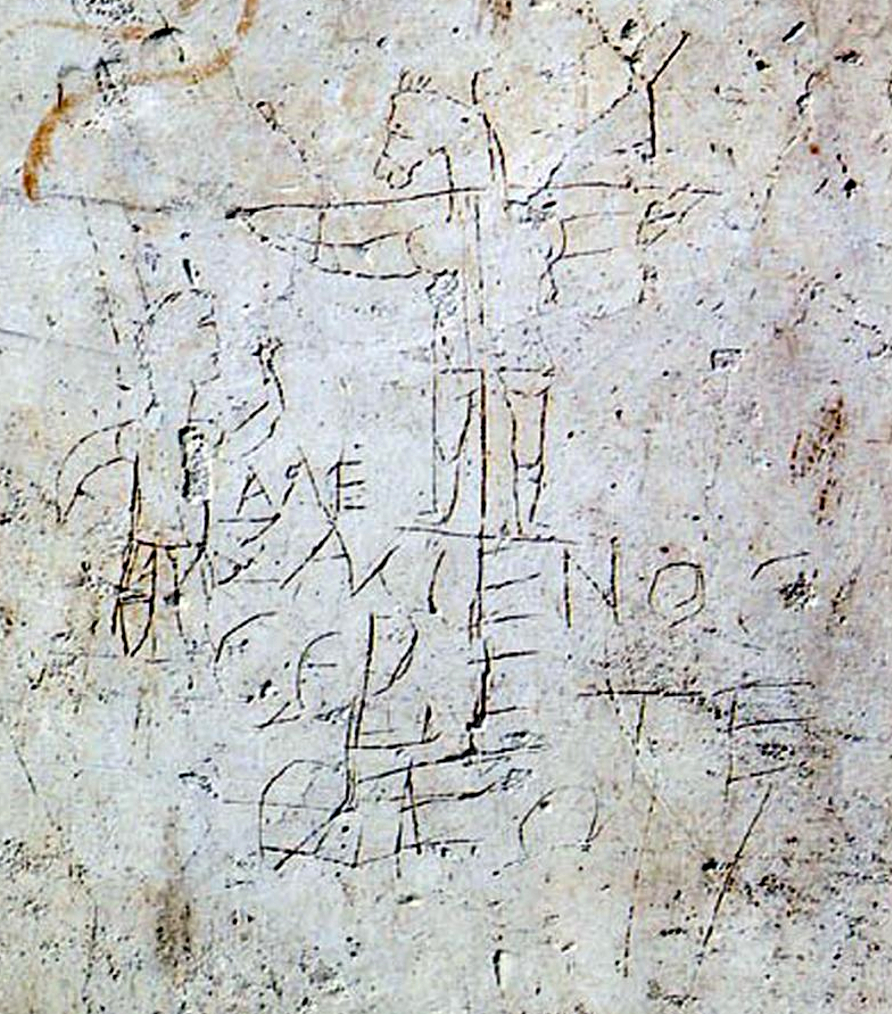

The response by the church to persecution and death made complete sense within a Jewish worldview. The believed that God had been a good world, a world which would, in spite of sin and evil, be restored and freed from these things. The believed that God had power over death, and specifically that they would be given resurrection bodies just like Jesus. God had the power to restore their bodies and free it from sin, even if they were devoured by lions or reduced to ashes. Like the Jewish martyrs in 2 Maccabees 7, the second century martyrs responded to an evil empire by clinging to the promise of resurrection.

What makes this most interesting for the study of early church history is that during the second century Gnosticism arose and began to trouble the church. So around 180AD Irenaeus wrote his famous five volume

Adversus Haereses (Against Heresies or On the Detection and Overthrow of Knowledge Falsely So Called) which described and contrasted Gnostic belief against apostolic Christian belief, warning believers of the false teachings. Not a monochrome belief, Gnosticism was “a syncretistic, trans-religious theosophy that drew from Christian, Jewish, Greek, Syrian, Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Persian sources, often simultaneously” (David B. Hart). In contrast to Christianity, it commonly held that the created matter was a result of a fall within the divine world, the result of a lesser being that God. And whereas Christianity believed that the world belong to Jesus, who would restore the world at the resurrection of the dead, Gnosticism taught a salvation/escape from the world for a select few “spiritual” people.

There has been a movement over the past 100 years to portray the Gnostics as the genuine Christians persecuted by the empire and vilified by the catholic church. And yet surprisingly it is hard to find any evidence for this. Perhaps though it is not all that surprising, as NT Wright explains: "Which Roman emperor would persecute anyone for reading the Gospel of Thomas [since it so closely reflected Greek thinking]?....It should be clear that the talk about a spiritual ‘resurrection’ in the sense used by [the Gnostic writings] could not be anything other than a late, drastic modification of Christian language." It was the radical doctrine of the resurrection that brought the wrath of the Roman Empire down not on Gnosticism, but on Christianity.

Authority

As the life of Jesus and the Apostles faded out of the church’s living memory, it was confronted with a new issue of authority. From around 100AD the Apostolic Fathers Clement and Ignatius began to empahaise the important role of the local bishop as a source of unity and order:

"Wherever the bishop appears, there let the people be; as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church." Ignatius, Letter to the Smyrnaeans.

However by the middle of the scond century the church had begun to wrestle with the question of scriptural authority. The Apostles had left the church a collection of writings that bore their authority – gospels, epistles and revelations that were written by the apostles or people closely associated with the apostles. But there was no uniform agreement on what works actually constituted the apostolic witness. The works of Clement and Ignatius reference or allude to almost all the books of the New Testament as we now have it, as well as the Old Testament, but there was no actual list. And not every church had access to this apostolic collection.

What spurred the church into action was the Pontian Bishop Marcion of Sinope (c. 85-160AD), who made his way from Pontus to Rome in 142AD. It was at this point that he caused a massive disturbance in the Roman church, publishing the first Christian Canon. Marcion refused to accept the Old Testament as scripture, arguing that its Jewish-ness was incompatible with the teaching of Jesus. He understood that God the Father of Christ and the God of Israel were different, which lead him to publish a truncated New Testament canon. Marcion’s canon was composed exclusively of just Luke (the

Evangelikon) and ten of Paul’s letters (the

Apostolikon), both of which were purged of references of Jesus' relationship with Israel.

Marcion was excommunicated from the Roman church in 144AD. The church’s response was to define the canon. The process began with the affirmation of the fourfold gospel canon of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John (the

Tetramorph); gospels received from the Apostles or their close associates.

The other gospel which emerged later, such as Thomas, differed from the Tetramorph in two important ways. Firstly, they were not Jewish and disdained a connection to Israel. Secondly, they were not gospels; rather than being a narrative of events they were for the most part a collection of sayings. Again the criterion for the epistles was evidence of apostolic association (the letter had to authored by an apostle or shown to have been written by a close colleague – which led to the exclusion of works such as The Shepherd of Hermas and the Didache which had sometimes been considered the equivalent of scripture). The process of clarifying the canon continued during the later half of the second century; the earliest evidence we have of this is a damaged and thus incomplete, bad Latin translation of the Muratorian Canon from the late 200’s:

“The third book of the Gospel is that according to Luke… The fourth… is that of John… the acts of all the apostles… As for the Epistles of Paul… To the Corinthians first, to the Ephesians second, to the Philippians third, to the Colossians fourth, to the Galatians fifth, to the Thessalonians sixth, to the Romans seventh… once more to the Corinthians and to the Thessalonians… one to Philemon, one to Titus, and two to Timothy… to the Laodiceans, [and] another to the Alexandrians, [both] forged in Paul's name to [further] the heresy of Marcion… the epistle of Jude and two of the above-mentioned (or, bearing the name of) John… and [the book of] Wisdom… We receive only the apocalypses of John and Peter, though some of us are not willing that the latter be read in church. But Hermas wrote the Shepherd very recently… And therefore it ought indeed to be read; but it cannot be read publicly to the people in church.”

The Canon was formalised in the third and fourth centuries at various Synods and Ecumenical Councils around the Mediterranean world. Yet what these councils did was to formalise a canon that was already largely agreed upon and in place by 200AD. Marcion would not be the first time that heresy would push the church towards clarity.

Reflections

As we’ve seen, the first and second century churches life and praxis was grounded in the story of Israel and Jesus. 20 Centuries later, is this the case for you and your church?

I always find the writing of the apostolic fathers and second century church to be encouraging and uplifting. Take for example Melito of Sardis homily on the Passover, written around 160AD:

"This is the one who like a lamb was carried off and like a sheep was sacrificed. He redeemed us from slavery to the cosmos as from the land of Egypt and loosed us from slavery to the devil as from the hand of Pharaoh. And he sealed us from our souls with his own Spirit and the lambs of our body with the his own blood. This is the one who covered death with his shame and made a mourner of the devil, just as Moses did Pharaoh. This is the one who struck lawlessness a blow and made injustice childless, as Moses did Egypt. This is the one who rescued us from slavery into liberty, from darkness into light, from death into life, from a tyranny into an eternal kingdom (and made us a new priesthood and a peculiar, eternal people)."

I can think of nothing better than to recommend that you acquaint with our brothers and sisters from this time by reading what they wrote themselves. Most of their writings are available on line, and I’ll mention them under the recommend reading below.

Recommend Reading

- Early Christian Writings, translated by Maxwell Stamforth, edited Betty Radice, Penguin Books, 1968.

- The Christological Controversy, translated and edited by Richard A. Norris, Fortress Press, 1980.

- Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, Richard Bauckham, Eerdmans, 2008.

- Judas and the Gospel of Jesus, NT Wright, SPCK, 2006.

- The Early Church – Revised Edition, Henry Chadwick, Penguin Books, 1993.

An excerpt from a most excellent sermon Archbishop Rowan Williams gave on Sunday in Harare, Zimbawe. Worth checking out:

An excerpt from a most excellent sermon Archbishop Rowan Williams gave on Sunday in Harare, Zimbawe. Worth checking out: