If you had to put your finger on what caused the rise of the church in the Roman world (and beyond) in the first four centuries AD, what would you suggest? Miracles (as Eusebis suggests)? The blood of the martyrs (as Tertullian suggests)? I'd be inclined to follow sociologist Rodney Stark's suggestion that it was through relational networks of family and friends.*

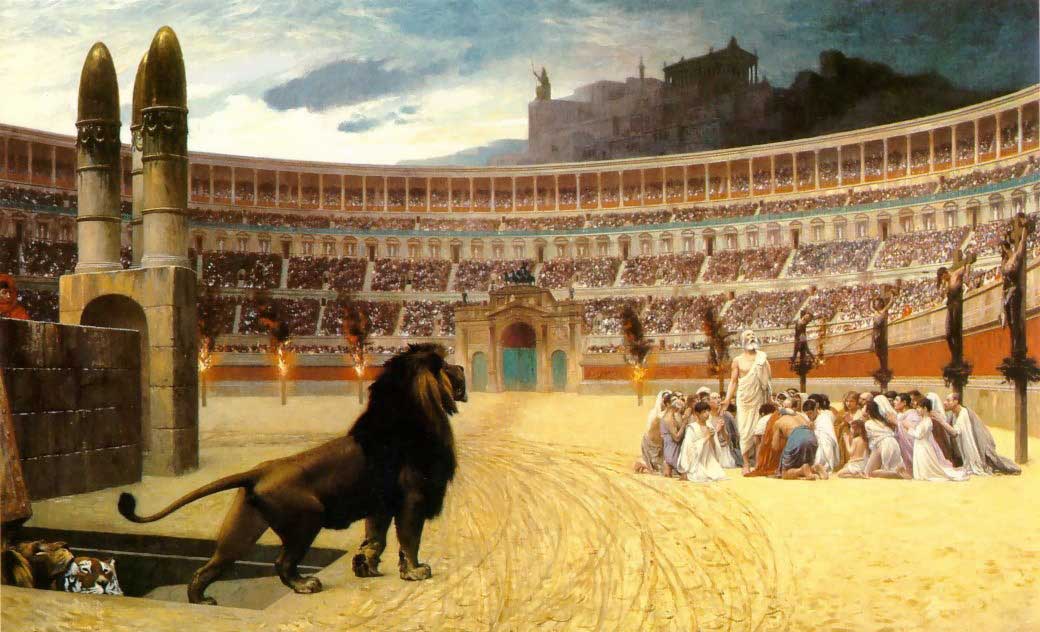

If you had to put your finger on what caused the rise of the church in the Roman world (and beyond) in the first four centuries AD, what would you suggest? Miracles (as Eusebis suggests)? The blood of the martyrs (as Tertullian suggests)? I'd be inclined to follow sociologist Rodney Stark's suggestion that it was through relational networks of family and friends.*According to Emperor Julian (b.331/332, d. 363), the last pagan emperor of the Roman Empire, the rise of Christianity in it's first four centuries - by the end of which at least half the empire was Christian - was the distinctive behaviour of Christians (which D.B. Hart includes as temperance, gentleness, lawfulness, and acts of supererogatory kindness) which were visible and appealing to their non-Christian neighbours. Julian wrote:

"It is [the Christians] philanthropy towards strangers, the care they take of the graves of the dead, and the affected sanctity with which they conduct their lives that have done most to spread their atheism." - Julian, Epistle 22 to Arsacius, the pagan priest of Galatia. Quoted by D.B. Hart in Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its fashionable Enemies, 2009.* Rodney Stark would also argue that it was Christian behavior that made it so attractive, particularity it's treatment of women.