A prayer, most likely written by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, in 1548 when England was at war with Scotland:

Most merciful God, the Granter of all peace and quietness, the Giver of all good gifts, the Defender of all nations, who hast willed all men to be accounted as our neighbours, and commanded us to love them as ourself, and not to hate our enemies, but rather to wish them, yea and also to do them good if we can: bow down thy holy and merciful eyes upon us, and look upon the small portion of earth which professeth thy holy name, and thy Son Jesu Christ. Give to all us desire of peace, unity, and quietness, and a speedy wearisomeness of all war, hostility, and enmity to all them that be our enemies; that we and they may, in one heart and charitable agreement, praise thy most holy name, and reform our lives to thy godly commandments. And especially have an eye to this small isle of Britain. And that which was begun by thy great and infinite mercy and love, to the unity and concord of both the nations, that the Scottish men and we might for ever live hereafter, in one love and amity, knit into one nation, by the most happy and godly marriage of the King’s Majesty our sovereign Lord, and the young Scottish Queen: whereunto promises and agreements hath been heretofore most firmly made by human order: Grant, O Lord, that the same might go forward, and that our sons’ sons, and all our posterity hereafter, may feel the benefit and commodity of thy great gift of unity, granted in our days. Confound all those that worketh against it: let not their counsel prevail: diminish their strength: lay thy sword of punishment upon them that interrupteth this godly peace; or rather convert their hearts to the better way, and make them embrace that unity and peace which shall be most for thy glory, and the profit of both the realms. Put away from us all war and hostility, and if we be driven thereto, hold thy holy and strong power and defence over us: be our garrison, our shield, and buckler. And seeing we seek but a perpetual amity and concord, and performance of quietness promised in thy name, pursue the same with us, and send thy holy angels to be our aiders, that either none at all, or else so little loss and effusion of Christian blood as can, be made thereby. Look not, O Lord, upon our sins, or the sins of our enemies, what they deserve; but have regard to thy most plenteous and abundant mercy, which passeth all thy works, being so infinite and marvellous. Do this, O Lord, for thy Son’s sake, Jesu Christ.

Sunday, November 11, 2018

Wednesday, September 19, 2018

The War on Waste

This week I started using a bamboo toothbrush. They’ve been in the cupboard for a while, and I’ve had to wait until my I’d finished with my last plastic one. It’s part of a concerted effort on our part to more thoughtful about our environmental impact.

The reusable coffee cups came at the start of the year.

Then after the latest season of ABC’s The War on Waste we installed a little worm farm on our balcony.

There have been moments of failure along the way - every time I’ve forgotten to take bags with me on shopping trips. Or the wry judgment I’ve felt from friends when bartenders have placed a straw in my drink.

There have moments of abject confusion. A few weeks ago I stood at the bin, with a shredded and sticky mandarin peel in my hand, not knowing what to do with it. Should I put in the bin? (And thereby send some more methane into the ground). Or should I throw it on the garden nearby? (And thereby litter in a space where there are no composting worms. The only positive benefit along this route would perhaps be for the rats of Newtown). 34 years of formation kicked into the gear; the mandarin skin went into the bin.

I call it The War on Waste effect, and it says something of the measure that host Craig Reucassel has had on my moral sensibilities.

Similar to other work originating from The Chaser, it pursues information through entertainment. But more than the usual satire, War on Waste is a call to arms - a show that demands action. And what action has been taken. After only two seasons and a handful of episodes, the major supermarkets have banned single use plastic bags.

But I find it a fascinating show for what it reveals about firstly morality in our society, and secondly how Christians have responded to Reucassel’s call to arms.

On the first front, it’s undeniable that The War on Waste operates within a moral ecology with clearly defined ideas of what is right and what is wrong. This moralism is evidenced in Reucassel’s use of language such as right, wrong, and shame. There are warriors out there, fighting against the complacency and laziness which has led to some of the ecological challenges we face.

What the rhetoric of The War on Waste suggests is that the language of moral realism Christians have been ingesting for the last 40 years in their world view studies of “the West” may need to be taken with a pinch of salt.

In case it has been lost on anyone, the cultural moment we inhabit seems to believe in a moral universe, of some description. We are longer living in the days when the modernist pale misreading of postmodernism as relativism seems plausible. Instead we live in a society that can discriminate between good and bad, right and wrong. The rise of sectarian partisanship, the fragmenting if common objects of love within culture, the failure of cherished institutions to protect children or act with financial prudence, these have all contributed to a rise of anxiety in our society. It’s in this climate that we’ve seen the re-emergence of a secular Puritanism; a morality self-consciously convinced by its own obvious right-ness.

Christians in Australia have been increasing facing this trend for sometime now in several social ethic issues. From euthanasia to same-sex marriage, the arguments made by those outside the church have lacked the hallmarks of relativism. I’m the part of Sydney where I live, people are generally fairly happy to sign up to the golden rules, not harming others and loving their neighbours. And amongst the members of the boomer generation I know, they’re convinced that they have fulfilled all righteousness on this front.

You see, it’s not that people aren’t into objective truth any more. It’s just that increasingly, people reject the evangelical of objective truth.

On the Christian response to The War on Waste, the show once again reveals that in some of my Christian circles, there is an unwillingness or inability to connect ecological care with the Christian walk

On the one hand that isn’t surprising, given that responding to climate change has in some measure been the undoing of every Australian government since 2007.

On the other hand, among my individual Christian friends - the ones truth be told whom mostly are not Anglican ministers - there has been a willingness to try something - anything - to make a difference.

I read one response to The War on Waste a little while ago that thoughtfully sought to engage with the program. At the end, it draw the conclusion that recycling etc is ok, but don’t get the wrong idea about saving the world because only God does that. And the only reason therefore to think about cycling and caring for the planet is because of the second of the two great commandments: “you shall love your neighbour as yourself.”

I found that an interesting conclusion to draw for two reasons. Firstly, whilst we inevitability watch The War on Waste in the context of grappling with climate change in a post Inconvenient Truth world, The War on Waste isn’t really about climate change. Grappling with e-Waste, preventing the degradation of marine life, or learning to recycle would all be good things to do anyway. Climate change or no climate change. Current ecological challenges gives recycling etc a greater clarity perhaps. But exercising responsible dominion over the earth would require to think through these issues even if we’re weren't facing global warming. For me personally, The War on Waste has exposed settled habits and patterns of behaviour that would otherwise lead to complacency and an abdication of our responsibility to the rest of creation. So seeking to reduce waste is not driven by a misguided eschatology, it’s about wise responsibility.

Secondly, it is becoming increasingly common in Evangelical circles to say that protecting our planet only makes sense in light of the second of the two great commandments. That is, environmental responsibility only makes sense Christianly out of love for our neighbours. Which is partially true; sustainable care of the earth is an act of love for our neighbours. Ecological degradation through CO2 emissions, global warming, nuclear and industrial waste, etc harms and kills our neighbours. But it’s only partially true.

Take this recent example from Moore College’s Lionel Windsor: “We have a responsibility to do what is right out of love of our neighbour, not out of saving the world.”

I find this to be a curious move to make. It’s not too dissimilar to the view of the Inner West baby boomers I met who are convinced of their own goodness because of their ability to meet this requirement.

I think it’s a sub-Christian argument. Not because love of neighbour is irrelevant for environmental action. But because the first of the two great commands is also relevant. That is, Windsor’s argument is anthropological rather than theological, and fails to recognise that one might seek to limit your wastage and your overall ecological footprint out of your love for God.

After all, don’t we read time and time again in the Scriptures that the non-human creatures don’t exist for us, even though they live in closely bound relationships with us. They exist for God:

The young lions roar for their prey, seeking their food from God. – Psalm 104:21

There go the ships, and Leviathan, which you formed to play with. – Psalm 104:26

Praise the LORD from the earth, you great sea creatures and all deeps, fire and hail, snow and mist, stormy wind fulfilling his word!

Mountains and all hills, fruit trees and all cedars!

Beasts and all livestock, creeping things and flying birds! – Psalm 148:7-10

All things exist for the praise and delight of God their creator. If we needed any convincing of this, the stirring account of the magnificent Jesus in Colossians 1 underscores this point with triple underlines:

For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities-all things were created through him and for him. – Colossians 1:16

Preserving biodiversity, exercising wisdom in dealing with our waste, resisting the impulse to consume – each of these can be pursued out of a love for neighbour AND a love for the God who delights in his creation and made a world that is beautifully diverse. Moreover, the gospel of the kingdom calls us to repent our selfish desires and forsake the innate need we have to consume at the expense of other creatures. The world doesn’t exist for us. David writes that ‘The earth is the Lord’s, and the fullness thereof.’ This is true, regardless of any environmental emergency. It is time to attend once more to this doctrine, and allow it to shape our love and obedience of God as we live in the world he has made.

Thursday, June 14, 2018

When I was Younger

When I was younger

it was always

it was always

the sea

that allured me:

the depth of the cerulean waters,

the foam of the waves,

the cry of the gull

the sting of the salt and the sand on my pale, apocalyptic legs.

The sea, the sea, sung its siren song to me.

But I have put away childish things.

It’s the mountains I long for now.

Those same sandstone ridges I walked and climbed and scrapped me knees on as a juvenile.

Once scorned for the sea,

whenever I’m by the water I find myself peering for those familiar peaks,

the deeply hewn valleys guarded by stones sentinels,

the smell of new rain among the gums,

and the blue haze on the horizon.

Beyond the towers of the city

it’s the plateaus and summits and bluffs that I look for,

and the glimmer of gold on stone that keeps at bay

the shadow and the gloom.

Monday, February 12, 2018

The Irony of Secularism

Last week I was away for work on the fringe of Sydney, without mobile reception or FM radio. That left me, on my occasional drives into town for supplies, with the glories of AM radio. Memories of my childhood come flooding back as I drove through scrubland with the static crackling from the stereo, and re-discovering that the signal noticebaly improved at night.

During one drive into town I was treated with an extended interview on atheism with a minister, a journalist, and a former politician. Whilst the segment was meant to cover the viability of atheism today in Australia, the former politican was pushing for a broader conversation about free thinking and secularism. It turned out that he was a spokeperson for a secular lobby group that seeks to dismantle the co-operative existence of the church and state in Australian society and impliment in its place a strict segregation between the two.

It was ultimatley an unfulfiled interview. The philosophical and historical illiteracy of one of the participants frustrated things somewhat. In particular, any deed or action by the church in the public sphere was dismissed as the imposition of Christian belief in society. Instead what Australia needs is the negative liberty of freedom from religion.

What was clear from the conversation was the general assumption that secularism is a neutral position. Secularism is an objective position; secularism favours no religion above another, and honours those of no religious affiliation. This is a mistaken position on several fronts; for our purposes we shall limit ourselves to only one: secularism is the creation of Christianity. By and large secularism has existed and flourished in places where the church has, over centuries, significantly shaped the social imaginary. Secularism is part of the Christian understanding of the world.

The concept of secularism emerged in the writings of Augustine of Hippo in the early 400s. As refugees sailed across the Mediterranean from Italy to North Africa fleeing barbaric violence in and around Rome, Augustine's musings on the decline of the 'eternal city' and the permanence of the true eternal and celestial city developed into a substantial theory of politics and jurisprudence. Drawing upon the writings of the Apostle Paul and other New Testament authors, Augustine recognized that the authority of the government has been limited to a penultimate role - namely the call to humbly provide justice. Government of any type are charged with responsibility of upholding the common good by commending what is right and condemning what is wrong. It is a penultimate role according to Paul and others, because our governments will one day have to give an account for their use of power, and governments are deprived of the legitimacy to claim our ultimate allegiance and affection.

This is the Christian concept of secular. The word “secular” has come to mean “non-religious”; but it was never meant to mean that. “Secular” comes from the Latin word saeculum, which means “age.” So “secular government” means “government in this age”. [Augustine was well aware that because something belonged to this age did not preclude it from God's care or will. The fact that marriage belongs to this age does not imply that God is either indifferent to marriage or has nothing to say on the subject]. The opposite of “secular” is not “sacred” but “eternal”. The distinction between sacred and secular, between the "heavenly city"and the "earthly city" is one of seemingly of time (thought ultimatley of love). The distinction between the Earthly City and the Heavenly City is the recognition that the secular authority and the church belong to different stages of salvation history. It is a difference primarily of eschatology, and secularism invovles the recognition that authority of government has been relegated.

Good government recognises that is limit, that is, secular. As British ethicist Oliver O'Donovan has describd it:

Nonetheless, the modern malaise notwithstanding, secularism emerged out of Christian reflection that a. the rulers of this world will need one day to throw their crowns before Jesus in submission, and b. governments cannot regulate the inner workings of our heart and mind. Secularism is part of the Christian deduction of the way the world works.

The irony therefore, of contemorpary secularism is that by imposing secularism on society, you are imposing a Christian vision of society.

During one drive into town I was treated with an extended interview on atheism with a minister, a journalist, and a former politician. Whilst the segment was meant to cover the viability of atheism today in Australia, the former politican was pushing for a broader conversation about free thinking and secularism. It turned out that he was a spokeperson for a secular lobby group that seeks to dismantle the co-operative existence of the church and state in Australian society and impliment in its place a strict segregation between the two.

It was ultimatley an unfulfiled interview. The philosophical and historical illiteracy of one of the participants frustrated things somewhat. In particular, any deed or action by the church in the public sphere was dismissed as the imposition of Christian belief in society. Instead what Australia needs is the negative liberty of freedom from religion.

What was clear from the conversation was the general assumption that secularism is a neutral position. Secularism is an objective position; secularism favours no religion above another, and honours those of no religious affiliation. This is a mistaken position on several fronts; for our purposes we shall limit ourselves to only one: secularism is the creation of Christianity. By and large secularism has existed and flourished in places where the church has, over centuries, significantly shaped the social imaginary. Secularism is part of the Christian understanding of the world.

The concept of secularism emerged in the writings of Augustine of Hippo in the early 400s. As refugees sailed across the Mediterranean from Italy to North Africa fleeing barbaric violence in and around Rome, Augustine's musings on the decline of the 'eternal city' and the permanence of the true eternal and celestial city developed into a substantial theory of politics and jurisprudence. Drawing upon the writings of the Apostle Paul and other New Testament authors, Augustine recognized that the authority of the government has been limited to a penultimate role - namely the call to humbly provide justice. Government of any type are charged with responsibility of upholding the common good by commending what is right and condemning what is wrong. It is a penultimate role according to Paul and others, because our governments will one day have to give an account for their use of power, and governments are deprived of the legitimacy to claim our ultimate allegiance and affection.

This is the Christian concept of secular. The word “secular” has come to mean “non-religious”; but it was never meant to mean that. “Secular” comes from the Latin word saeculum, which means “age.” So “secular government” means “government in this age”. [Augustine was well aware that because something belonged to this age did not preclude it from God's care or will. The fact that marriage belongs to this age does not imply that God is either indifferent to marriage or has nothing to say on the subject]. The opposite of “secular” is not “sacred” but “eternal”. The distinction between sacred and secular, between the "heavenly city"and the "earthly city" is one of seemingly of time (thought ultimatley of love). The distinction between the Earthly City and the Heavenly City is the recognition that the secular authority and the church belong to different stages of salvation history. It is a difference primarily of eschatology, and secularism invovles the recognition that authority of government has been relegated.

Good government recognises that is limit, that is, secular. As British ethicist Oliver O'Donovan has describd it:

“The most truly Christian state understands itself most thoroughly as secular. It makes the confession of Christ’s victory and accepts the relegation of its own authority… The essential element in the conversion of the ruling power is the change in its self-understanding and its manner of government to suit the dawning age of Christ’s own rule.”What we have witnessed in the modern age is a forgetfulness of what it means to be secular. In abandoning the eschatological vision which makes the secular possible, society has walked away from the very thing which made it possible im the first place. Isntead society has become obsesseded with mediation of meaning through advertising, publicity, and advertising rather than the enactment of justice.

Nonetheless, the modern malaise notwithstanding, secularism emerged out of Christian reflection that a. the rulers of this world will need one day to throw their crowns before Jesus in submission, and b. governments cannot regulate the inner workings of our heart and mind. Secularism is part of the Christian deduction of the way the world works.

The irony therefore, of contemorpary secularism is that by imposing secularism on society, you are imposing a Christian vision of society.

Friday, January 12, 2018

Dispatches from Australia 3

The headline in the Sydney Morning Herald (somewhat provactly) read:

Responding to the decline of occupied shops along Sydney's Oxford Street strip, Max Raine of Raine & Horne suggested that an 'underutilised' church in Paddington should be demolished in an effort to revive the historic shopping precinct. According to the SMH article:

Raine's suggestion came somewhat of a surprise not only to the congregations of St Matthias, but also many Christians in Sydney and further afield - St Matthias being a vibrant inner-city parish.

However, Raine's suggestion fits neatly into a narrative that Australian's are increasingly telling each other: Christianity is on the decline, and church attendance numbers are insignificant. (Despite this narrative, Australians are more likely to attend a church service during the year than a sporting event or the cinema).

I encountered the full force of this narrative in 2013 during a D.A. process with my previous church. We wanted to build a ministry centre adjacent to the Victorian church building to provide much needed space for milling around, disabled access, and toilets accessible during church services. The D.A. proposal sparked opposition from a segment of the community who set themselves up as the Save the Church lobby group. During two council hearings about the DA, the opposition group repeatedly ran the line that the Ministry Centre was unneccesary because less than 20 people attended the church on Sundays (at the time the reality was closer to 200 - there were at least 50 church members in the council chambers audience at the time).

Instead, the D.A. was obviously the work of corporate greed, and these fairminded citizens where the last line of defence for the the sandstone building and four acres of land their suburbs founders had left 'for the people of this suburb'. Never mind the fact that the four acres of land had been purchased by the church for divine worship. Never mind the fact that it was the church community driving the D.A. so that the church could be more hospitable.

Their incongruity at the church's need was fueled by the narrative that Christianity is on the decline, etc. The fact that the church was sizeable, and full of people in their 20s (and not just grannies) didn't fit in their plausability structure, and therefore couldn't be true.

They knew best what the church needed.

Demolish St Matthias church, build massive Oxford Street car park, says property tycoon (21 July 2014).

Responding to the decline of occupied shops along Sydney's Oxford Street strip, Max Raine of Raine & Horne suggested that an 'underutilised' church in Paddington should be demolished in an effort to revive the historic shopping precinct. According to the SMH article:

St Matthias Anglican Church was “hardly attended” yet occupies a “glorious spot” near the corner of Oxford Street and Moore Park Road, which [Raine] claimed was ripe for conversion into a parking station.

Raine's suggestion came somewhat of a surprise not only to the congregations of St Matthias, but also many Christians in Sydney and further afield - St Matthias being a vibrant inner-city parish.

However, Raine's suggestion fits neatly into a narrative that Australian's are increasingly telling each other: Christianity is on the decline, and church attendance numbers are insignificant. (Despite this narrative, Australians are more likely to attend a church service during the year than a sporting event or the cinema).

I encountered the full force of this narrative in 2013 during a D.A. process with my previous church. We wanted to build a ministry centre adjacent to the Victorian church building to provide much needed space for milling around, disabled access, and toilets accessible during church services. The D.A. proposal sparked opposition from a segment of the community who set themselves up as the Save the Church lobby group. During two council hearings about the DA, the opposition group repeatedly ran the line that the Ministry Centre was unneccesary because less than 20 people attended the church on Sundays (at the time the reality was closer to 200 - there were at least 50 church members in the council chambers audience at the time).

Instead, the D.A. was obviously the work of corporate greed, and these fairminded citizens where the last line of defence for the the sandstone building and four acres of land their suburbs founders had left 'for the people of this suburb'. Never mind the fact that the four acres of land had been purchased by the church for divine worship. Never mind the fact that it was the church community driving the D.A. so that the church could be more hospitable.

Their incongruity at the church's need was fueled by the narrative that Christianity is on the decline, etc. The fact that the church was sizeable, and full of people in their 20s (and not just grannies) didn't fit in their plausability structure, and therefore couldn't be true.

They knew best what the church needed.

Tuesday, January 02, 2018

Dispatches from Australia 2

In their famous 1989 book Resident Aliens, Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon describe the end of a world - the capitulation of Christendom to secularism - in 1963 when a local cinema opened on a Sunday.

I started school in 1990. It was a state school on the urban fringe of Sydney. About half the buildings at the time were demountables. In between learning to tie my shoes and get through the day without a nap, there was a whole new "liturgy" that I had to learn. In particular, there were two sets of words the student body was expected to know.

That world has long since past. For me, it disappeared almost in the twinkle of an eye, and had vanished by the time I started my second year at primary school. With the weight of globalization as the cold war ended, along with a rising sense of an Australian identity, republicanism, multiculturalism, and an increased awareness of our indigenous heritage, it's surprising that I even encountered these two sets of words regularly at school in the first place.

It would be tempting though to ascribe their disappearance to the irreversible tide of secularism, which seems to sweep Australia with increasing ferocity every five years as census results are announced. According to popular assumption, religion is occupying a declining space in public ad private life, and eventually will all but vanish from Australian life (except for indigenous religion apparently, because that can explained away as "cultural").

It might just be that Christendom took longer to root out from Australia's Blue Mountains than it did to the American South. Admittedly, Australia has a long and complicated relationship between faith and society. But amidst those complications, Australia has been, by and large, accommodating (e.g. not antagonistic) towards religion. And the truth of the matter is that secularism is not a new phenomenon in Australia; it has been with European Australia since 1786 when Richard Johnson was appointed Chaplain to the First Fleet.

Although it may come to a surprise, secularism is a thoroughly Christian achievement. The word “secular” has come to mean “non-religious”; drop by any P&C meeting these days and when the world "secular" is used, it is understood to be in opposition to faith and organised religion. But it was never meant to mean that. “Secular” comes from the Latin word saeculum, which means “age.” It was developed by Augustine of Hippo to account for the now and not yet eschatological tension Christians find themselves in. By definition, the opposite of “secular” is not “sacred” but “eternal”. So “secular ” means “of this age” rather than the eternal.

Secularism actually is a consequence of the gospel of Jesus Christ, which announces that all earthly governments have been relegated to penultimate status. The Australian government is not eternal. Each and every government is secular because there will come a time when the governments of the world cast their crowns before the lamb who was slain. As Oliver O’Donovan has helpfully written:

With the ascension of Jesus Christ, secularism is the stripping of governments of their pretensions to command our absolute and whole-hearted obeisance.

Rather than the rise of secularism then, I wonder perhaps what we have witnessed in Australia over recent decades is the loosening of our common bonds. The traditions and institutions which have served our society have gradually been weakened and become unintelligible to us. Philosophically, concepts such as secularism and representation have become gibberish to us, unmoored as they are to their original intent and purpose. Whatever the case, we may have reached a point expected by several cultural commentators, who foresaw it with a sense of joy (Nietzsche), sadness (Tolkien), or despair (TS Eliot).

For O'Donovan, it actually is an occasion for chastened optimism for gospel opportunities in a society like ours. He writes that "Western civilization finds itself the heir of political institutions and traditions which it values without any clear idea why, or to what extent, it values them." Christian witness and theology has an opportunity to shed light on institutions and traditions whose intelligibility is seriously threatened. There is an apologetic value for Christians to think theologically about politics during a crisis of confidence in our politics. This is unlikely to result in a return to the situation of my primary school in 1990. That may not even be desirable. However, what is needed from Australian Christians is a commitment to our institutions and society at large for the sake of the common good because we know Jesus' lordship over all things. To do so would be to swim against the current and buck the trend that has dominate western societies at large since the 1960s (at least). But perhaps Christians are at their best in society when their swimming against the general trends.

I started school in 1990. It was a state school on the urban fringe of Sydney. About half the buildings at the time were demountables. In between learning to tie my shoes and get through the day without a nap, there was a whole new "liturgy" that I had to learn. In particular, there were two sets of words the student body was expected to know.

- The first was a song that was sung every few weeks at the school's formal assembly. It turned out this song was God Save the Queen, which had only been relegated from Australia's national anthem to Australia's royal anthem several years earlier when the graduating year of 1990 had started school (i.e. 1984). Looking back on it now, and the painting of Queen Elizabeth II from the late 1960s which hung in the office, my primary school feels like sometimes it would be at home on The Crown.

- The second, I would come to learn, was The Lord's Prayer, which was said at least once per week during school assembly. As we stood in straight-ish lines on the asphalt quad, the older years would recite the prayer from memory - Protestant bit and all.

That world has long since past. For me, it disappeared almost in the twinkle of an eye, and had vanished by the time I started my second year at primary school. With the weight of globalization as the cold war ended, along with a rising sense of an Australian identity, republicanism, multiculturalism, and an increased awareness of our indigenous heritage, it's surprising that I even encountered these two sets of words regularly at school in the first place.

It would be tempting though to ascribe their disappearance to the irreversible tide of secularism, which seems to sweep Australia with increasing ferocity every five years as census results are announced. According to popular assumption, religion is occupying a declining space in public ad private life, and eventually will all but vanish from Australian life (except for indigenous religion apparently, because that can explained away as "cultural").

It might just be that Christendom took longer to root out from Australia's Blue Mountains than it did to the American South. Admittedly, Australia has a long and complicated relationship between faith and society. But amidst those complications, Australia has been, by and large, accommodating (e.g. not antagonistic) towards religion. And the truth of the matter is that secularism is not a new phenomenon in Australia; it has been with European Australia since 1786 when Richard Johnson was appointed Chaplain to the First Fleet.

Although it may come to a surprise, secularism is a thoroughly Christian achievement. The word “secular” has come to mean “non-religious”; drop by any P&C meeting these days and when the world "secular" is used, it is understood to be in opposition to faith and organised religion. But it was never meant to mean that. “Secular” comes from the Latin word saeculum, which means “age.” It was developed by Augustine of Hippo to account for the now and not yet eschatological tension Christians find themselves in. By definition, the opposite of “secular” is not “sacred” but “eternal”. So “secular ” means “of this age” rather than the eternal.

Secularism actually is a consequence of the gospel of Jesus Christ, which announces that all earthly governments have been relegated to penultimate status. The Australian government is not eternal. Each and every government is secular because there will come a time when the governments of the world cast their crowns before the lamb who was slain. As Oliver O’Donovan has helpfully written:

“The most truly Christian state understands itself most thoroughly as “secular”. It makes the confession of Christ’s victory and accepts the relegation of its own authority… The essential element in the conversion of the ruling power is the change in its self-understanding and its manner of government to suit the dawning age of Christ’s own rule.”

With the ascension of Jesus Christ, secularism is the stripping of governments of their pretensions to command our absolute and whole-hearted obeisance.

Rather than the rise of secularism then, I wonder perhaps what we have witnessed in Australia over recent decades is the loosening of our common bonds. The traditions and institutions which have served our society have gradually been weakened and become unintelligible to us. Philosophically, concepts such as secularism and representation have become gibberish to us, unmoored as they are to their original intent and purpose. Whatever the case, we may have reached a point expected by several cultural commentators, who foresaw it with a sense of joy (Nietzsche), sadness (Tolkien), or despair (TS Eliot).

For O'Donovan, it actually is an occasion for chastened optimism for gospel opportunities in a society like ours. He writes that "Western civilization finds itself the heir of political institutions and traditions which it values without any clear idea why, or to what extent, it values them." Christian witness and theology has an opportunity to shed light on institutions and traditions whose intelligibility is seriously threatened. There is an apologetic value for Christians to think theologically about politics during a crisis of confidence in our politics. This is unlikely to result in a return to the situation of my primary school in 1990. That may not even be desirable. However, what is needed from Australian Christians is a commitment to our institutions and society at large for the sake of the common good because we know Jesus' lordship over all things. To do so would be to swim against the current and buck the trend that has dominate western societies at large since the 1960s (at least). But perhaps Christians are at their best in society when their swimming against the general trends.

Monday, January 01, 2018

Dispatches from Australia 1

"Everything in this country is socialist!"I dined late last year with a visitor to Australia's shores, who, as you might tell from the brief exchange above, had reached (in his mind) a damning conclusion about Australia. Its institutions, its people, its very DNA all smelt of socialism.

"Everything?"

"Everything. Your health care system. The ABC. Your university admissions. The fact that you have a minimum wage. It's all socialist!"

Admittedly, compared to the homeland of my fellow dinner, Australia is in a unique position. Many of our institutions are in public hands (and when I was a kid many were publicly owned, such as the Commonwealth Bank, Telstra, The State Bank in NSW, etc.), and many aspects of our welfare system, such as Medicare, have taken on the status of an institution, such that it would be close to politically impossible for a government to dismantle them.

However, rather than socialism, I suspect that these aspects of Australian society bear witness to an older political tradition. We are called ‘the Commonwealth of Australia’, which oddly at first only looks as if we share riches, as in ‘common wealth’. This is, of course, partially true: we do share riches in terms of participating in an economy, and using common infrastructures. But that economic truth is only one aspect of a deeper truth that was once being expressed by this term. ‘Wealth’ comes from an older word for what is good, ‘weal’, hence a ‘commonwealth’ was always meant to be about a society of people committed to a ‘common good’.

Just pointing out the name of the country does not nothing on its own. However, Andrew Cameron has argued that 'The fact that we were called a ‘Commonwealth’ indicates that there has been an alternative tradition at work in Australia: the concept of a community who seeks together for a good life, in quality relationships with one another.'

[There is a long Christian history of the common good drawing on the significant New Testament word koinonia, which can traced, among other places, in Oliver O'Donovan's short book Common Objects of Love.]

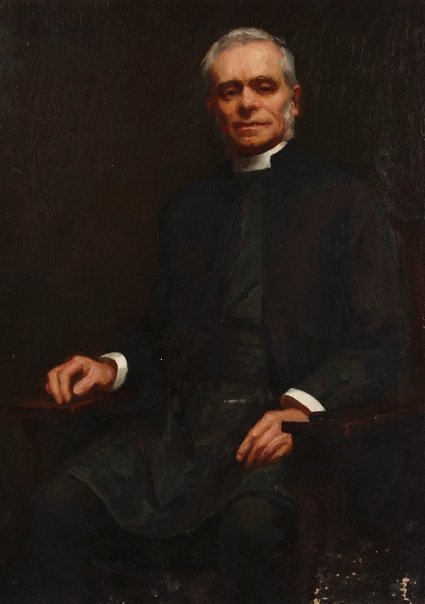

Arguably, it is this concept of society which drove the introduction of the pension in NSW. One of the significant forces behind the introduction of old-aged and infirm pensions in NSW was the Ven. Francis 'Bertie Boyce and the now defunct the parish of St Paul's Redfern. Boyce was hardly a socialist; as the founder of the British Empire League, he tirelessly campaigned for the observance of Empire Day in NSW - it helped that the Premier of NSW was a member of St Paul's. Boyce also founded the Anglican Church League, the conservative evangelical lobby group in the Sydney Diocese.

It may come as a surprise to you then that Boyce was the leading social reform advocate in NSW at the turn of the 20th century, covering issues such as woman's suffrage, slum clearance, and temperance. Boyce has advocated for years on the issue of an old aged pension. The introduction of the pension was a significant moment in NSW, as it had by and large been the responsibility of the church to provide relief for the aged. Yet Boyce did not see this as a straight handing over to the state the relief work which had traditionally been the purview of the churches. Preaching at St Paul’s Redfern just after the introduction of the pensions into NSW, Boyce described the expected £60,000 p.a. cost of the pension as ‘a Christian contribution to suffering humanity.’

Whereas the church had previously been limited by its connections with those in need and its own fundraising, for Boyce the government's new found responsibility to provide the pension would move beyond the limited connections any one church might have and enable as many people to be cared for in their twilight years. Reflecting on Romans 13 and 1 Peter 2, Boyce argued that this would give the Christian all the more reason to pay their tax, and to see their tax used in the service of those in need by God's own ministers.

At a time when we read about individuals and corporations peddling their money through overseas tax havens, Boyce's approach to tax and welfare seems entirely foreign. And yet, it's beautiful, and based on a generous ecclessiology - that the church exists as the pillar and bulwark of truth to extend God's blessing to all people in society.

Far from socialist, the bedrock for Australia's great institutions rest upon a Christian concept of of community.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)