The Unimpressive Church

The Unimpressive Church

Intro | Part I | Part II | Part III | AppendixThe student of ecclesiastical history may often be left with the impression that for three hundred years the story of the church was solely the story of leaders and scholars. The kind of men you’d find being represented in an icon; men like Polycarp and Irenaeus, or Tertullian and Origen. It is easy to tell the story of the leaders of the church. They were the men (for they were mostly men) who took the gospel to new parts of the world, who continued to freshly articulate the significance of Jesus to life and thought, who defended the faith, who taught God’s word, and who would sometimes lose their lives for Jesus’ sake. They were impressive people, and it’s easy to think that by understanding their story you have understood the whole.

Yet that does not give us the full picture. By the third century (200-300AD) there were hundreds of thousands and even millions of Christians spread throughout the Roman world, the Persian empire, in Armenia (the first official Christian state), Arabia, Ethiopia and India. And by focusing on the bishops and scholars can leave us with an all too grand picture of what the early church looked like (particularly when compared to more familiar church history).

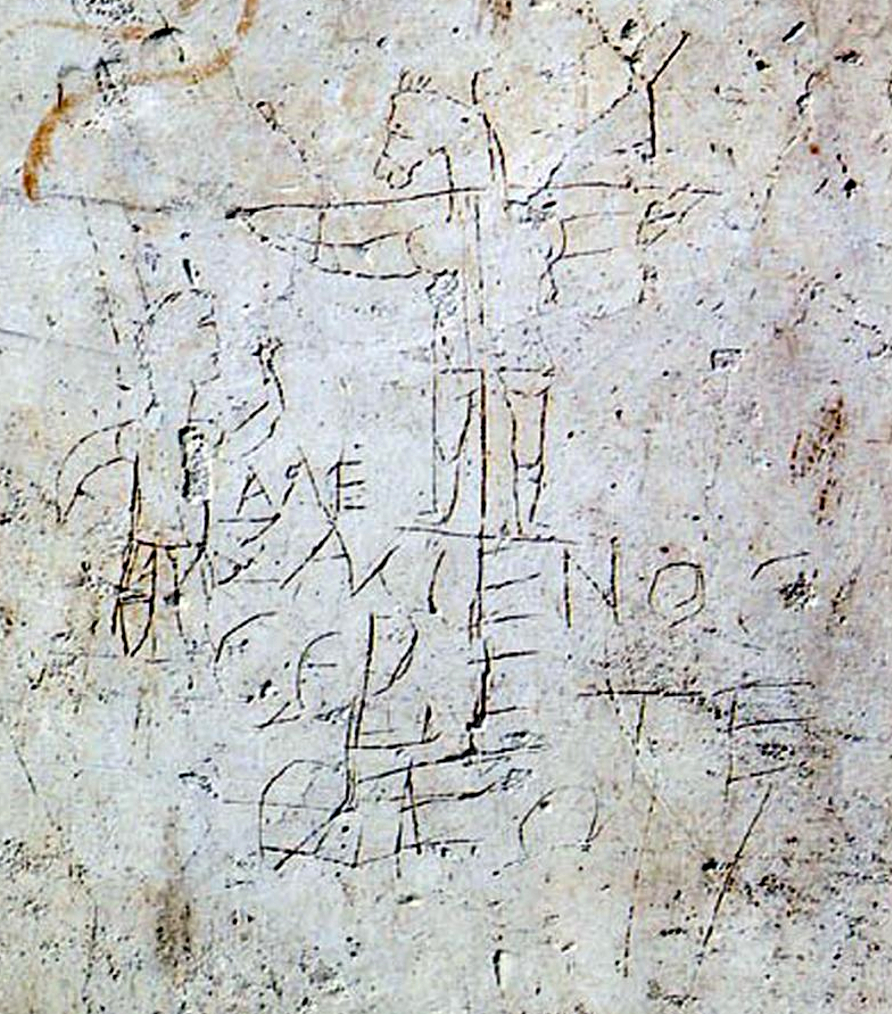

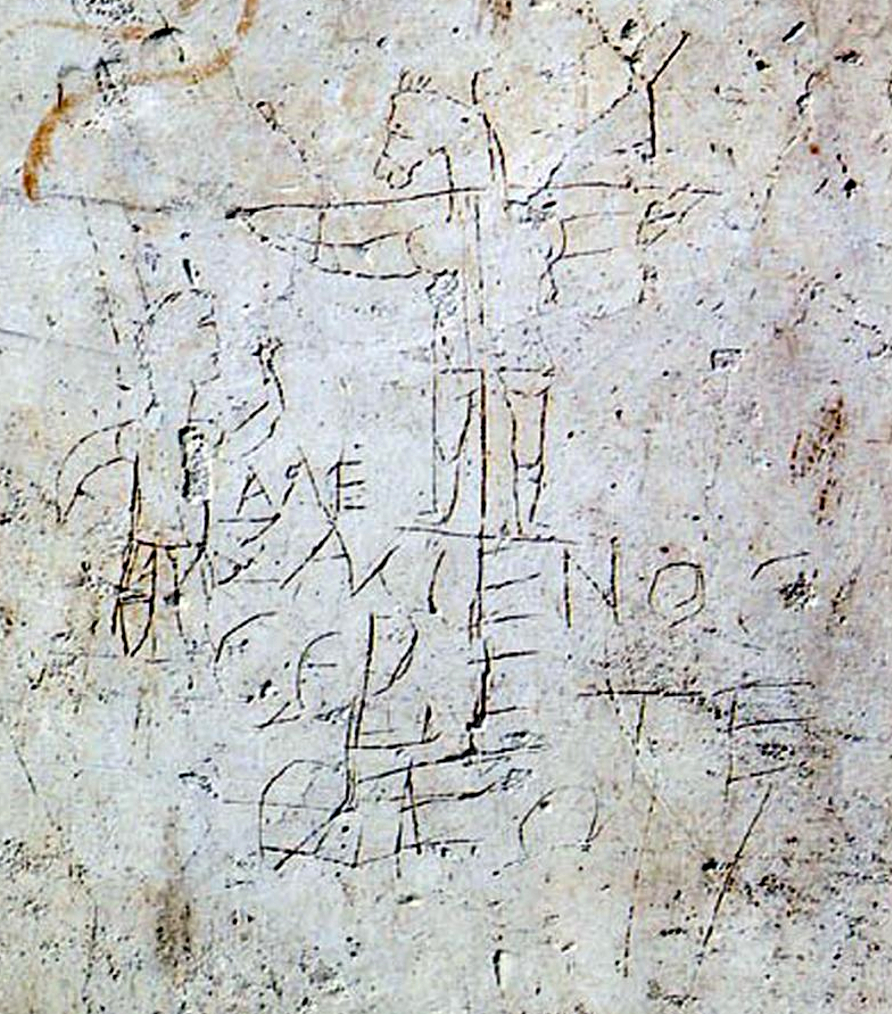

The dominant feature of the early church is how utterly unimpressive it was. This might seem strange, given the rapid speed with which Christianity spread around the known world. But as the Apostle Paul reminded the Corinthian church: “not many of you were wise according to worldly standards, not many were powerful, not many were of noble birth”. The church was distinctively ordinary. Although there were Christians from all sections of society, a high proportion of Christians came from what we might call a humble background. And this made the church scandalously ordinary, as men AND women from every class and status would welcome one another. When its critics looked at the church, what they saw was the basest kinds of humans sordidly meeting together for their ‘love feasts’ (an early name for the Eucharist). You can feel this scandal in the writing of Celsus, a second century critic of the church who wrote that it is:

“...only foolish and low individuals, and persons devoid of perception, and slaves, and women, and children, of whom the teachers of the divine word wish to make converts”.

The church became contemptuously known for holding slaves and women in high regard. For this it was seen to be unravelling the very fabrics of society. Inside the church slaves could hold positions of leadership, i.e. deacons, presbyters; even outrageously leading their owners if they too were Christian. And in the Roman world as more and more people became to Christian, they abandoned the ancient gods – the very same gods who ensured the peace and prosperity of the empire. This is one reason why we see such a vitriolic reaction against Christians during the reign of Emperor Diocletian at the end of the third and into the fourth century.

Not only was Christianity unimpressive, it was also dangerously subversive to order and security of the world. But who were the early Christians?

It is no understatement to describe Christianity as an urban movement. The church was so heavily represented in the cities of the Mediterranean, that the word for people who lived in rural areas came to be used to describe anyone who was not a Christian. We know it today in English as pagan.

By the third century an increasing number of new Christians came from a non- Jewish background. It was not typically through the mass conversions we often imagine; people became Christian as their family and friends witnessed to them in both word and deed. New believers would be welcomed into the “family of believers” each year at Easter. They would continue to meet together each Sunday to celebrate the Lord’s Day. And excluded to the margins of society and under the threat of death, the church continued to live by its convictions. The second century Epistle to Diognetus described the early Christians in this way:

For the Christians are distinguished from other men neither by country, nor language, no the customs which they observe. For they neither inhabit cities of their own, nor employ a peculiar form of speech, nor lead a life which is marked out by any singularity... But inhabiting the Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. They marry, as do all [others]; they beget children; but they do not destroy their offspring. They have a common table, but not a common bed. They are in the flesh, but they do not live after the flesh. They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws by their lives... To sum up all in one word - what the soul is to the body, that are Christians in the world.

As unimpressive as the church was, there was something radically impressive about it as well. According to academics like Rodney Stark and David Bentley Hart, this has to do with the Christian concept of humanity. The church understood itself to be a new humanity. They were a family, the “brethren”, established by Jesus to welcome everyone. So that is what they did. In the words of Hart, the church gave a face to the faceless, welcoming those who technically had no identity in society. Slaves were welcomed and able to participate in the church. Furthermore, the church welcomed and valued women. Throughout the empire, there were a higher proportion of men to women. The affects of female infanticide and abortions that often resulted in the death of the women created this gender imbalance. However, it appears that there was an opposite gender imbalance in the church, with more women than man. The church was the sole community in the empire that condemned these practices and gave women the dignity due to them being created in God’s image.

The church was also known for acting on this conviction outside the Christian community, caring for the poor and sick and the well being of their cities. They became so well know for it that the last “pagan” Emperor Julian, in the fourth century, lamented that:

“These impious Galileans [Christians] not only feed their own poor, but ours also; welcoming them into their agapae [love feasts], they attract them, as children are attracted, with cakes.”

The church proclaimed the gospel of Jesus in both word and deed. This was particularly seen in two epidemics between 250AD and 350AD that devastated the eastern half of the empire. 10,000’s of people died, and whilst the rich and elite “pagans” fled the cities, it was the Christians who stayed and cared for the sick and dying:

“[During the great epidemic] most of our brother Christians showed unbounded love and loyalty, never sparing themselves... Heedless of danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ... Many, in nursing the curing others, transferred their death to themselves and died in their stead... The [pagans] behaved in the very opposite way. At the first onset of the disease, they pushed the sufferers away and fled even from their dearest, throwing them into the roads before they were dead." - Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria , circa 260AD.

These were the early Christians. They lived out the gospel in their lives and in their actions. And unlike a lot of Christians today, they didn’t have any hang-ups about what proportion the needed to that they in. They just did it; even if it cost them their lives. In the face of terrible persecution (which we haven’t covered in this post), social exclusion, and death, they lived out the gospel, welcoming everyone who claimed allegiance to Jesus. This was the terribly ordinary, unimpressive church. Not many of them were wise; not many of them were powerful. “But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong” (1 Cor 1.27).

For Further Reading:

- David Bentley Hart, Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies, 2009. Winner of the prestigious Michael Ramsay Prize for 2011, Atheist Delusions offers great insight on the early church and the world around it.

- Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity, 1997.

- Rodney Stark, Cities of God, 2006.

- Henry Chadwick, The Penguin History of the Church: The Early Church, (revised edition), 1993.

The old man looked the missionary in the eye: “You keep telling us about how sinful we are and how we need to change, but no one ever says this to the white people who steal our land, our wives and our daughters. No one says this to the men who are killing us..."

The old man looked the missionary in the eye: “You keep telling us about how sinful we are and how we need to change, but no one ever says this to the white people who steal our land, our wives and our daughters. No one says this to the men who are killing us..."